Yesterday, 25 March, marked the centennial of the last New Zealand soldiers of the NZEF leaving Europe. The Expeditionary Force was officially disbanded thereafter and so New Zealand’s greatest contribution to WWI came to an end. Things had been winding down since the New Zealanders had marched into Germany as part of the Army of Occupation (stationed at Cologne) in December 1918. The gradual return of men to New Zealand had already seen the two Otago infantry battalions amalgamated (on 4 February) into a single Otago Battalion. Within weeks, on 27 February, the Otago and Canterbury Battalions were also amalgamated to become C and D Company respectively of a South Island Battalion. It must have been a strange time for everyone involved. The intensity of life under the stresses and strains of active service had suddenly, and somewhat unexpectedly to many, been released with the signing of the Armistice on 11 November 1918. Making the transition back to normal life for the citizen soldiers of the New Zealand forces would be a challenging process.

New Zealand troops march into Cologne, Germany, December 1918. Alexander Turnbull Library, 1/2-013770-G.

For the administrators, getting all those men back to New Zealand as quickly as possible was the immediate logistical challenge. A shortage of shipping options complicated matters, with the British controllers of the transport system having a different set of priorities and their own challenges to overcome. For many of the soldiers it would be a long wait and as the influenza panedemic continued to take its toll, some would never in fact get home. Stuck in overcrowded army camps in the bleak setting of the Salisbury Plain through a cold northern winter and forced to undertake education programmes that held little appeal for many, these frustrations eventually boiled over. On 15 March 1919 hundreds of the soldiers at Sling Camp rioted, looting the stores for alcohol and cigarettes and trashing the officers’ messes. It was one of the worst breakdowns in New Zealand army discipline of the whole war.

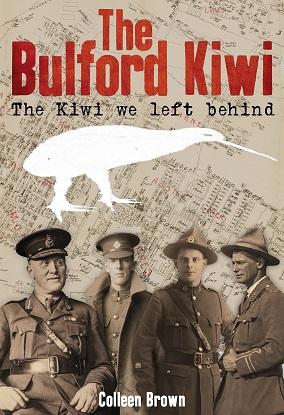

The Army’s response was to meet the men half-way, reducing the compulsory education programmes and giving them something else to do. For the Otago men, along with those of other New Zealand regiments, this involved cutting the shape of a giant kiwi into the chalk of the hill overlooking the camp at Bulford. Though not a member of the Otago Regiment, it was a Dunedin-born soldier Victor Low who did the complicated surveying work to mark out the shape of the kiwi on the hillside. Low was a member of New Zealand’s earliest Chinese family, and along with his brother Norman one of a small number of Chinese New Zealanders who served with the NZEF. The work to excavate the kiwi symbol in the chalk hillside began in April and continued right through until 28 June, the day the Treaty of Versailles was signed to formally end the war. The kiwi survives to this day, one of the more unusual memorials to the New Zealand contribution to Britain’s war effort and a reminder of the tens of thousands of men who spent hard months of training on the Salisbury Plain. In 2017 the British Government listed the Buklford Kiwi as a scheduled monument, recognising its heritage status officially and according it a measure of protection for the future. Its story was told in full for the first time last year with the publication of Colleen Brown’s book The Bulford Kiwi – The Kiwi We Left Behind.

And then it was home time. Troopship followed troopship, making the long journey halfway around the world to return the soldiers to a country many hadn’t seen for years. What must it have been like for them, and for those who awaited their return so eagerly? They all carried a burden from their time away. Some were physically shattered and would never fully recover. Others were scarred mentally in ways that would blight the rest of their lives. All carried a psychological burden that few others would ever be able to understand. Looking back over the century, with an increased awareness of post traumatic stress disorders, we can only wonder how families managed to cope with all these difficulties in the post-war years. It is a story that remains to be told.

The band on a troopship returning to New Zealand, 1919.

Private Robert Wallace Watson of the 1st Otago Infantry Battalion had been wounded three times and died from his injuries in Dunedin hospital in January 1921.

But this blog was established with a more limited purpose: to follow the unfolding centennial of the Otago men who took the path to war in 1914, the Otago Infantry Regiment and the Otago Mounted Rifles who together were “the Otagos”. With their journey completed, so too does this blog come to an end. It has been an honour to remember all the triumphs and tragedies along the way, and most especially to walk in the footsteps of the soldiers in making our Journey of the Otagos documentary. This remains available on You Tube and hopefully will long serve as a resource for those wanting to know more about the Otago units’ experiences in the Great War. Thanks to all those who have followed the journey with me and for the input and feedback received.

Duty done.