Today is 7 June 2017, the centenary of the Battle of Messines in New Zealand. As I write it has just passed 1pm and through the vagaries of international datelines and daylight savings in Europe this is actually the moment when the great advance began. It was 3.10am in the morning in Belgium when the earth shook and the sky erupted in flame and shattered earth as 19 enormous mines were detonated simultaneously in a ring along the Messines Ridge. The mines had been carefully prepared over the previous two years by British, Canadian and Australian tunnellers who drove long shafts into the ridge under the German lines. These were then packed with massive amounts of explosive and primed for firing as the opening salvo of the Messines attack, a prelude to the major 1917 British offensive known as the 3rd Battle of Ypres.

General Haig, the overall commander of the British forces, has long wanted to mount an offensive in Flanders but wider strategic and political considerations had seen the 1916 attack mounted instead further south at the Somme. We’ve already noted how badly the Somme campaign ended up for the Otagos and the New Zealand Division, with losses on a scale that dwarfed the casualties from Gallipoli. They had come up against the reality of a war of attrition where the industrialised nature and scale of the conflict simply chewed up men and material and spat them out. And all for so little; the strategic gains of the Somme campaign were so modest compared to its aims and the relatively small area of ground that had been won. To cap it all off, after the conclusion of the active phase of the Somme offensive the Germans pulled back 40 kilometres, simply handing over much of the ground that had cost so much blood. Their new positions had been carefully prepared, a formidable array of defensive structures on ground selected to favour its defenders that was collectively known to the Germans as the Siegfried Stellung and to the Allies as the Hindenburg Line.

Now in 1917, however, the Somme was set aside and Haig was finally to mount his Flanders campaign, with the ultimate goal of driving through the German defensive lines to the railway junction at Roulers and from there northward to the Belgian coast. Taking the German U-boat bases there would deal a fatal blow to the German submarine campaign that was proving so disruptive to Allied shipping. It might well be the death knell of the German war effort. The first step, however, would be to take the Messines Ridge which overlooked the Ypres salient and gave the Germans higher ground from which to observe Allied activity. Pushing them off this high ground was a prerequisite in setting up for the grand breakthrough it was hoped would follow.

The preparation that had gone into the Messines attack were impressive. The mines under the German lines were one part of it. So too was the massive logistical exercise to bring forward all of the guns, munitions, and supplies that would be required once the action got under way. Equally important, however, were the new tactics based around a “bite and hold” co-ordination of artillery and infantry movement within a limited and tightly defined set of advances. The men would move forward under a curtain of shell fire, pausing for it to lift off the German positions and move to the next target as the infantry surged forward to overwhelm the German defenders. This required great skill in fire and movement on both parts and was practiced extensively by the New Zealanders in the months before the battle. Replicas of the German trenches were dug and even a large-scale model of the Messines Ridge and its defences. Every New Zealand officer was trained on it while the men worked up their platoon-level development of specialized weapons and movement in co-ordinated waves. Everybody knew their job and what had to be done.

New Zealand troops training for Messines: Ref: 1/2-012753-G. Alexander Turnbull Library.

The scale of the attack was considerable. Twelve divisions were to advance along a 16-kilometer front with the II Anzac Corps on the right-hand side of the line. This put the New Zealand Division at a position opposite the ruined village of Messines itself. They were to take the village in two forward jumps as defined by a Brown Line and a Black Line, setting up for a further Australian advance to a Green Line beyond the village. The New Zealand advance would be on a two-brigade front about 1500 metres wide, with the 2nd Brigade on the left and the 3rd Rifle Brigade on the right. The dividing line between them was roughly along the roadline that is now called Nieuwzealanderstraat (New Zealander Street).

The Messines Ridge from Spanbroekmolen crater – the Otagos attacked up the slope on the right toward the village

Within the 2nd New Zealand Brigade sector, it was the 1st Otago Battalion and the 1st Canterbury Battalion at right who would lead the attack. Their objective was to take out the German trench lines on the slopes of the hill leading up to the village, move on and secure the village itself and then form a new defensive line along its eastern side. The 2nd Otago Battalion was in reserve, its job to mop up and consolidate positions on the western slope of the hill. It was a carefully considered plan, well prepared and with every man aware of the job ahead of him. The artillery had been preparing the ground since 21 May, destroying German gun batteries and cutting the wire all along the line. There would be the added massive disruption of the mine detonations to start the attack and then an overwhelming bombardment from 2266 guns, one for every 6.5 metres of line. As soon as the mines went off, they would drench the German lines with shells and explosives. Fire would rain down on the German positions along the western slope of Messines at the same time as a creeping barrage would move ahead of the advancing infantry until they were right on top of the German trenches. And it all went like clockwork.

The Spanbroekmolen Crater – today ‘The Pool of Peace”.

At zero hour, 3.10am, 19of the 21 mines erupted under the German lines. The ground for miles around shook as if an earthquake had struck. For the Germans in their trenches the effect was devastating. Up to 10,000 men are believed to have died from the explosions with the survivors shaken into complete discombobulation. The huge craters left in the ground today stand as mute testimony to the horror, notwithstanding the softening effect of vegetation and water at a place like the “Pool of Peace” as the Spanbroekmolen crater is known today. There were no mines in the immediate vicinity of the New Zealand Division but six of the detonations could be seen from their positions and the ground rocked beneath their feet as Captain Lindsay Inglis recorded:

As the big guns opened, every near object showed clear cut in the light of their flashes. At the same moment six great fans of crimson flame slowly expanded upwards from the other side of the valley. The ground rocked beneath us as in an earthquake … In less than a minute the whole face of the Messines Ridge was submerged in billowing clouds of dust and smoke.

With that, the race was on. The infantry set off under the creeping artillery barrage, a wall of steel moving forward ahead of them, moving quickly forward uphill towards the German defenders. It wasn’t far and they reached the first trenches within minutes. The German machine-gunners had taken shelter in their concrete bunkers and were trapped by the advancing troops before they could scramble back to position and get their guns up and firing. As Colonel Stewart recorded in his history of the New Zealand Division:

On the battered and blocked line of dirt, timber, wore-netting, concrete and dead, which was all that remained of the once splendid trenches of the front system, the whole attack had poured so swiftly that the Germans had no opportunity to resist. They were bombed in their dugouts or bayoneted within two yards of them.

Looking down from the German positions in 2013. This was slope up which the Otagos attacked in the early morning of 7 June 1917.

It was a signal triumph and Messines was taken quickly and with relatively few casualties. Similar success had been achieved all along the line to Wytschaete, such that the Messines Ridge had fallen, pushing the Germans back 3 kilometres along an arc from the Douve River to Mount Sorrel, in the greatest British victory of the war to date. It was too good to last. As the Germans consolidated in new positions beyond the ridge, they began to shell their old positions with deadly effect. The New Zealand troops crowded within Messines village and along the top of the ridge were easy targets and casualty numbers rose steadily through the day. General Russell the New Zealand Division commander sought to thin his line by pulling back one Brigade but his request was refused by Godley concerned about a concerted German counter-attack. In the end the New Zealand Divisions lost 3,700 men at Messines, killed, wounded or missing. Many of these losses were because of the overcrowding on the ridgeline after the morning’s successful attack.

This morning’s Otago Daily Times was full of memorial notices for men killed at Messines a century ago. The Commonwealth War Graves website records 77 men from the Otago Regiment who died on 7 June 1917 and are buried in Belgian soil. Many more were wounded and lots of them would die from their wounds in the days and months that followed. It was a great victory but it had come at a fearful cost. Two of the fallen have particular resonance for me. One is my cousin Michael Scannell from Lyalldale in South Canterbury who was in the Canterbury Infantry Regiment and died on 7 June at Messines. Michael went away to war at the same time as my grandfather and was a very fine man by all accounts. It grieves me that his body was lost on the battlefield. I have had the privilege of visiting the Memorial to the Missing at Messines on two occasions to find his name and leave a poppy.

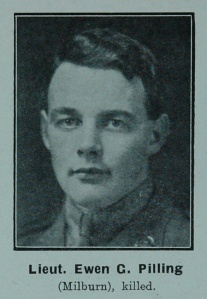

The other is Ewen Pilling whose exploits at Gallipoli featured so strongly in this blog two years ago. Ewen was selected for officer training after Gallipoli and thus missed the Somme campaign. He came back to New Zealand and spent some precious time back in Otago with his family and friends. He went overseas again with the 17th Reinforcements in September 1916 as a second lieutenant. He was killed early in the attack on Messines, being shot in the head a few minutes after leading his platoon over the parapet. A fellow old boy who knew Pilling well wrote to Otago Boys High – his old school – about his death:

As an old schoolmate of Pilling’s I am able to say that there have been few Old Boys of recent years more loved or more generally popular among us. As a fellow-soldier of his on active service, I have authority to add to that opinion a wider one, the estimation of men who had not known him in civilian life but who judged him solely on his merits in that great testing place of character, the field of battle. They learned to love and respect him as much as we. I did not belong to the same company as Pilling, but there was a legend throughout our battalion how, in the terrible days of August 1915, when all the officers were out of action, he took forward the line himself, sergeant as he was then, with great coolness and initiative … I have not known anyone straighter or more chivalrous; yet he did not stand aloof, but by his kindness to all and his wide sympathy became endeared to the roughest of us. Our loss may not be repaired. Our victories would need to be great indeed if they cost us the lives of men such as Pilling.