Thursday 19 June. Our last day on the road. We take the car back to Paris tomorrow and catch a plane to Hamburg. So what should we do today? Two ideas occurred to me. First, a return to Paris to find the spots we failed to get last week during our disastrous foray into the city. I looked into cancelling our last night’s booking at the hotel in Bailleul and relocating to Paris but we couldn’t. So to go to Paris would mean 2.5 hours driving there, and then back again, only to have to repeat the journey in the morning. Not such a big deal really when we had come all this way already. Then there was Etaples. Will had asked me to go there if possible because it was such an important staging post for British operations on the Western Front. It looked quite close to Bailleul (1.5 hours away according to the GPS). So that was the plan for the day: across country to Etaples on the coast, then down to Paris.

Etaples was huge, as well as hugely important, in 1914-18. The camp that developed around the railway connections there became an army city with up to 100,000 people there at any one time at its peak. There were 22 army hospitals, catering for 22,000 patients. It was also the training centre for the British Armies before troops were sent on to the front. All the soldiers had to undergo weeks of intensive training here, long hours in the sand dunes north of the town at what was called The Bull Ring. They hated it. The instructors were a vicious bunch, known as “canaries” for the yellow arm bands they wore. Not having been to the actual front themselves, these guys seem to have taken delight in subjecting their subjects to the harshest regime they could. They were despised by the soldiers, especially those with frontline experience who still had to pass through Etaples after suffering a casualty and recuperating in England. Before they could be re-integrated into the frontline force they were sent back to the Bull Ring at Etaples.

Tensions at Etaples erupted into the infamous mutiny in September 1917 (just before Passchendaele). This was set off by the arrest of a NZ gunner, caught out of bounds in Le Toquet, and the New Zealanders were heavily involved in the ensuing demonstrations. Etaples is also believed by British virologists to have been at the centre of the 1918 influenza pandemic, the origin of a precursor virus that swept the base in 1915-16. There was a specific New Zealand camp within the Etaples complex. I had found a map online that showed its location and this, and the Bull Ring area, were our targets. Of course, on the ground all that actually remains is the cemetery. But what a cemetery. It is the largest CWGC cemetery in France, with over 11,500 graves. Most are for those who died in the Etaples hospitals and there are 260 New Zealanders among them.

In fact, if you made it back to one of the General Hospitals at Etaples, having been wounded or gotten sick at the front, your chances of survival were pretty good. Only 6% of Etaples patients ended up dying. Medical services made great advances during WW1 and the system of dealing with casualties stretched all the way from Regimental Aid Posts, right up close to the action, through Casualty Clearing Stations a few miles back, and on to the hospitals. Survival rates improved dramatically as the system of triage and treatment developed and an evacuation infrastructure was created. If you look at a soldier’s service record you will often find references to this treatment route. It explains why someone like Dave Gallaher, wounded at Gravenstafel Spur, is buried at Nine Elms Cemetery, which is miles away behind Poperinghe and on the far side of Ypres. That’s near where he died, having been carried back through the medical stations.

Etaples 2014: thick forest and housing sub-divisions looked to cover the old camp site. There didn’t seem much point in looking for a relevant sand dune amidst the trees; the Bull Ring was out there to the left of the cemetery. We told the story accordingly. We also found an Otago man’s grave. Likewise with the old New Zealand camp sector. This didn’t look to be commemorated by any contemporary street names, for example (New Zealand Road didn’t take obviously. I picked a street corner that seemed a likely spot, just guessing from the old map, and told that story. Good enough Will? Etaples done.

Sunset over tents at the WWI NZ reinforcement camp, Etaples, France. Royal New Zealand Returned and Services’ Association :New Zealand official negatives, World War 1914-1918. Ref: 1/2-013018-G. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. http://natlib.govt.nz/records/22722937

William Massey and Joseph Ward salute New Zealand troops, Etaples, France. Royal New Zealand Returned and Services’ Association :New Zealand official negatives, World War 1914-1918. Ref: 1/2-013365-G. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. http://natlib.govt.nz/records/22699419

Then it was the 2.5 hour drive down to Paris. I’m not sure what the actual distance was but the road was fantastic. A three-lane highway with a 130 km/hr speed limit. Some super impressive viaducts and bridges. You have to pay to use this road – 16.50 Euros for us – but it is a very efficient way to travel. The toll collection points are incredibly quick too. You pull off the three lanes into a great wide bay with up to a dozen toll gates. They are all automated. When you begin your drive into a tolled section you pick up a ticket – like in any Dunedin automated parking building – and when you get to the end of the tolled section you feed the ticket into a matching set of toll gates. You put the credit card straight in after the ticket, the toll bar lifts and you’re off again.

The challenge for me on this next stage was driving into Paris itself. I had the location of Madame Yvonne’s and the Hotel D’Ostend (the two establishments Ettie Rout set up to cater for New Zealand soldiers on Paris leave). I wasn’t game to drive right into the central city zone where they were. But I thought I could cope with traffic out on the outskirts. I’d found a parking building in the north of the city where we could leave the car and get onto the Metro system. It was pretty hairy getting there – the GPS gave the directions but couldn’t help me with the crazy conditions at the intersections. I was really relieved when we reached the Rue De Porte Clignancourt unscathed. From here it was just a block to the Simplon metro station. We bought day passes, jumped on a train, and within minutes were outside Madame Yvonne’s. How could it have been so hard the previous Friday?

The difference was better planning and having my technological supports all working properly. That made it easy peasy. It was also a lovely sunny afternoon, there were no transport strikes, and everything just seemed to flow. The only question was, were the street numbers of 1918 still the same in 2014. We stopped for a drink at Rue St Lazare and I asked the locals. They were bemused by what we were looking for but pretty confident number 29 would be the same building. And there it was. A very fine building in a very smart street, now shops on the ground floor and apartments up above. Probably much the same back in WW1; Ettie aimed to take the sleaze and risk out of the soldiers’ sexual experiences and Madame Yvonne’s establishment was supposed to be a classy one.

The same was true for the Hotel’D’Ostend. It wasn’t far away but we took the Metro anyway. The hotel is still a hotel, now Hotel Noailles. In 1918 it was Ettie’s base and from it she provided New Zealand soldiers comfortable beds, good meals, a wamr welcome and advice. Some of the latter was about sexually hygiene, and included Ettie’s custom-designed prophylactic kit, but that wasn’t all it was about. Ettie was clearly devoted to the New Zealand men and did her best to make their Paris leave a safe and happy time. She was clearly a bit of an oddball (read Jane Tolerton’s biography and you’ll see what I mean) and way ahead of her time on sexual mores but there was no doubting her good intentions and she deserves to be remembered as “The Guardian Angel of the Anzacs”.

And that was that. Our 14-day Journey of the Otagos ended at 9 Rue de la Michoderie, well away from the battlefields but still covering one of the central experiences of the boys who set off for their big adventure overseas in 1914-18. It has been a real privilege to have this opportunity to walk in their footprints, from the rugged heights of Sari Bair, through the rich soils of the Somme and Flanders, and onto the smart streets of Paris. It’s been pretty hard work and I’m sorry if I’ve stressed that too much. I felt a heavy responsibility to deliver the goods when so much had been invested in getting us over here. Fortunately, everything panned out pretty well and apart from the long hours and the challenges of getting our stories right, it’s all worked out.

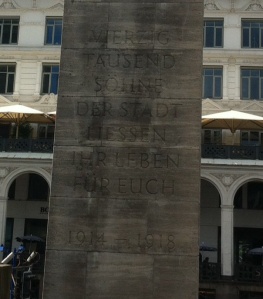

Now we just have to get the footage home, all 180 gigabytes of it. I’m afraid the postal option didn’t work out. I didn’t get to a post office in Paris and by the time we made enquiries with the Post Office in Hamburg we were too late. An express courier service was restricted to documents only. Our package of memory sticks would probably not reach New Zealand until we would. Sorry Will, I know that’s going to squeeze the timeframe for editing our footage for the exhibition. But at least there’ll be plenty to choose from. Joseph and I are on leave now and ironically we’re spending the next week in Hamburg, Germany where my eldest son lives. War memorialisation is much more problematic in Germany than New Zealand or France but I have seen two WW1 memorials since I got here (nothing for WW2). One noted that the city of Hamburg gave 40,000 of its sons in WW1. That’s worth remembering as we focus on our little part of the big story of the war: everybody suffered and no-one was immune from the cost of conflict.

In finishing this last entry of JOTO I want to thank all those people who helped get us here or helped us here: the WW1 commemoration fund of the Lotteries Commission, the Otago Settlers Association, and the DCC; Kirsty and Will for setting our trip up and being so enthusiastic about it; Steven at Mesen and Martin at Passchendaele and the Memorial Museum 1917 at Zonnebeke for their support and help. Thanks too for all the comments posted on the blog. Jo tells me it showed poor netiquette to not reply to each one. Sorry about that; I really appreciated the feedback anyway.

“In memory of the fallen sons of the world war 1914-1918”, St Mary’s Catholic church, Altona, Hamburg

JOTO is dedicated to the memory of all the members of the Otago Infantry Regiment and the Otago Mounted Rifles who lost their lives and rest far from their homeland. And to those who served and returned and suffered the consequences of their wartime experiences for the rest of their lives. May they all rest in peace.

Fantastic account by all means! Very much looking forward to seeing you tomorrow x

LikeLike

oh gosh – sad that its come to an end, its been very moving and have awaited each instalment (have been required to read it aloud which has been challenging when choked by the awful sad stories of lives lost). Have a good wee break now you’ve earned it

LikeLike